Commercial Hydrogen Engine with HPDI – Roadmap to High Efficiency, Zero CO₂ and Zero Pollutants

Published on June 17, 2025 · 6 min read

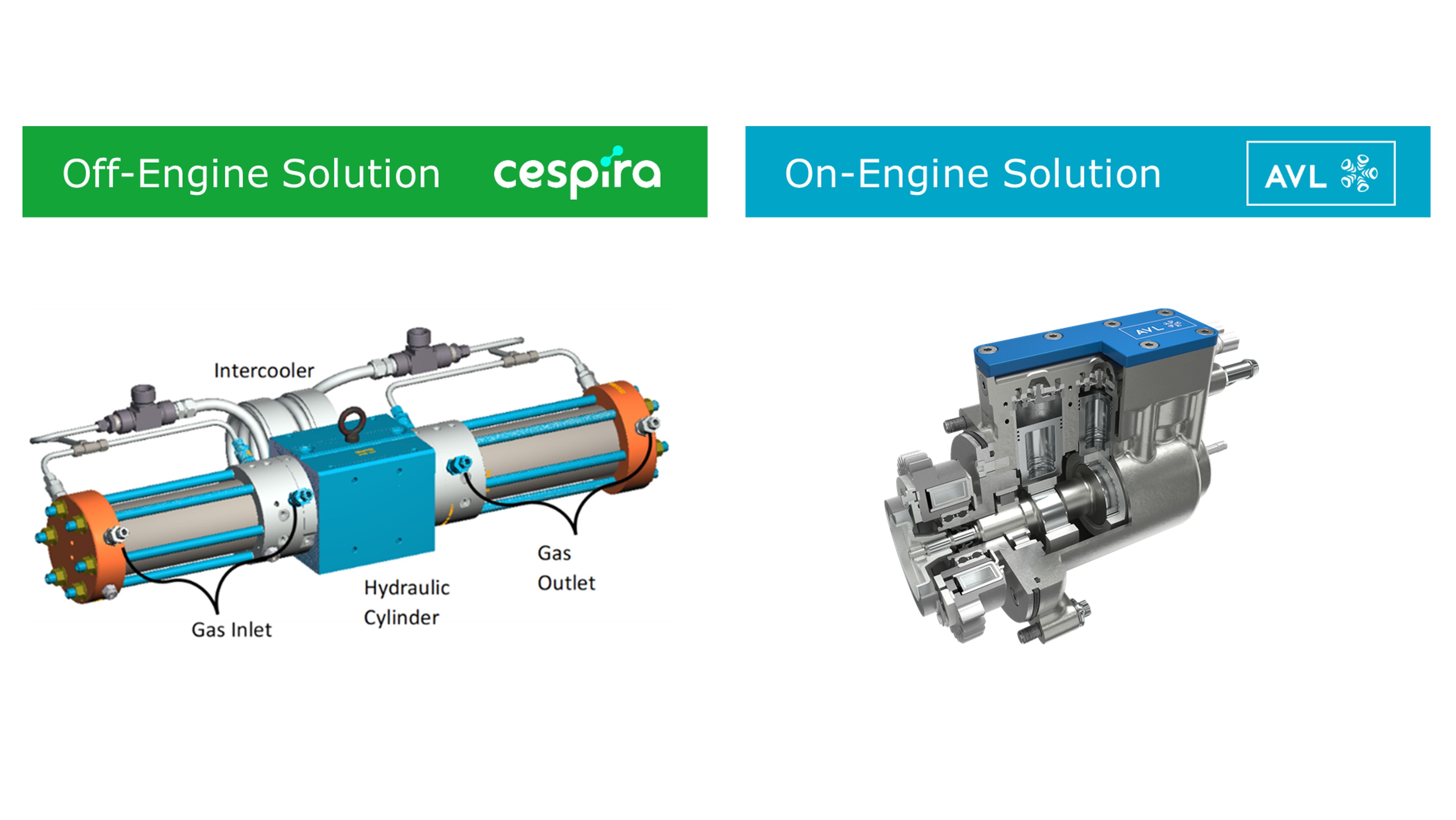

One of the main technical challenges for HPDI hydrogen engines – particularly when compared to spark-ignited concepts – is the need for high-pressure hydrogen supply. Injection pressures above 250 bar are necessary, which reduce the vehicle range unless onboard compression is implemented. To address this issue, several concepts are currently under development. Cespira is advancing an off-engine, hydraulically driven compressor system mounted on the truck chassis. Meanwhile, AVL has designed a compact, lightweight three-cylinder compressor that is directly driven by the engine. Both solutions represent viable approaches to enabling long-range HPDI hydrogen applications.

As previously demonstrated in AVL’s published expert article, H2-HPDI heavy-duty engines can achieve, when carefully developed, more than 50 % BTE. These results have been accompanied by the ability to maximize power density, an essential factor for commercial viability.

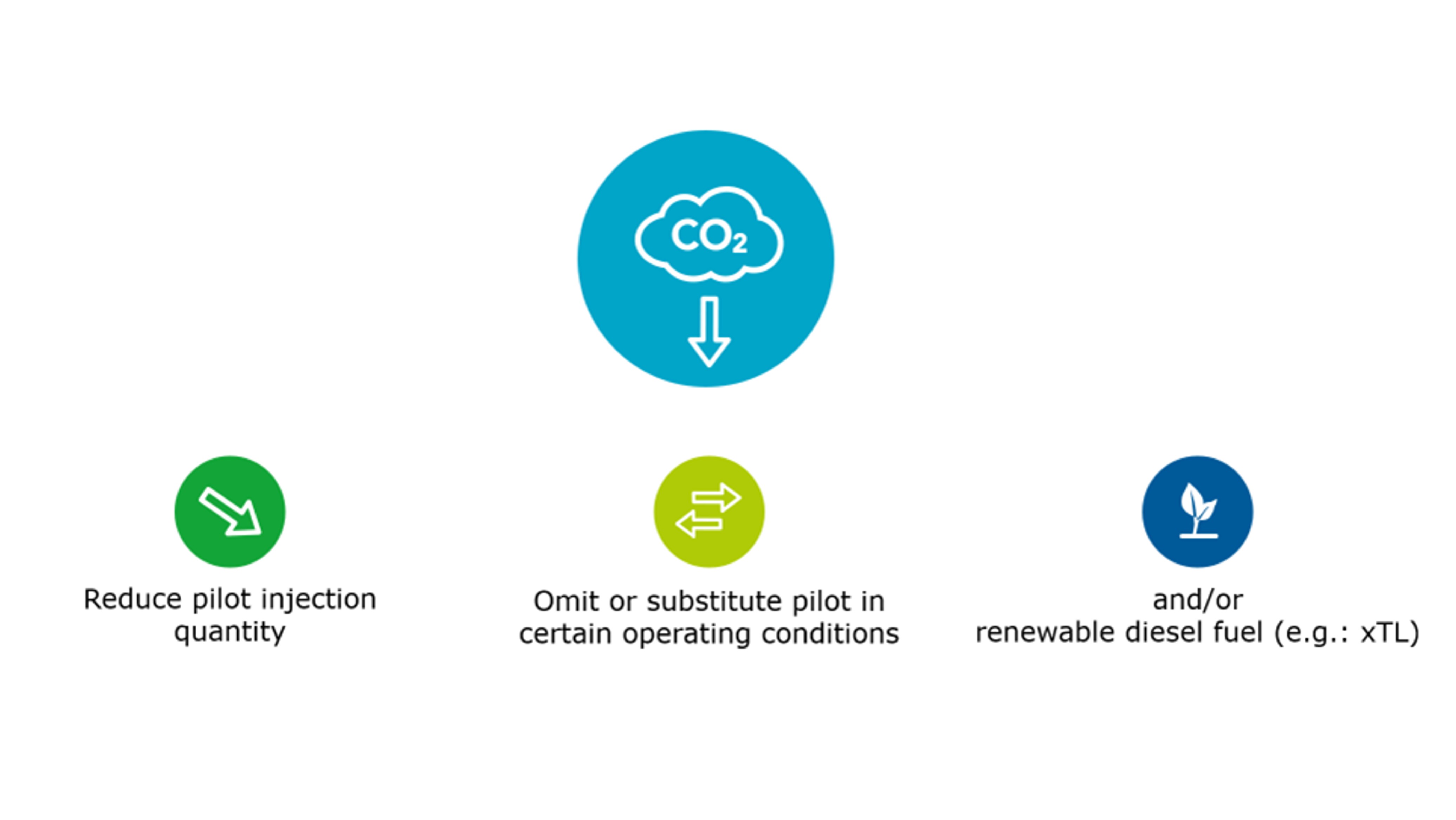

Since hydrogen combustion inherently produces no CO₂, the minimal carbon emissions from H₂-HPDI engines stem primarily from the small amount of liquid ignition promoter used to provide ignitable conditions for the hydrogen fuel. However, the CO2 emission is proven to remain below the EU’s Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) limit, as it can be reduced to less than 3 grams of CO₂ per ton-kilometer for heavy-duty long-haul truck cycle.

Further reductions in CO₂ emissions are achievable through three main strategies, each discussed in detail at the 2025 Vienna Motor Symposium and described in the accompanying manuscript. These include optimizing the combustion process through nozzle design (number and diameter of holes), partially substituting the pilot injection with an alternative ignition source, and finally, the most straightforward path, replacing diesel as the ignition promoter with HVO (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil) or other synthetic diesel fuels. These alternatives not only improve the well-to-wheel CO₂ footprint by further up to 90 % but also provide additional advantages.

Closed-cycle energy converters, which operate without a tailpipe, offer a promising complement to open-cycle combustion engines and electric drives in future. Although the concept is not entirely new, substantial research is still needed before these systems can be brought to market. However, ongoing advancements in hydrogen engines using HPDI, along with progress in solving the challenges of high-pressure supply, are significantly shortening the development path for closed-cycle engines.

Lund University is playing a leading role in establishing an international research consortium to explore noble gas closed-cycle power converters, closely cooperating with companies as AVL and SCANIA AB. Their new project, “Hectic – Highest Efficiency Hydrogen Energy Conversion with Lowest Negative Impact and Cost” funded by the Swedish Energy Agency, aims to address key challenges and identify opportunities in this field. The project includes advanced experiments and a global collaboration effort with major stakeholders in the transportation and energy sectors. Open development challenges, the rational for using Argon as working gas and the motivation for intensifying development efforts are listed below.

Once the HPDI hydrogen engine technology reaches fully maturity, transitioning to a closed-cycle engine operating with high-pressure hydrogen becomes feasible. These engines require hydrogen and oxygen, both readily available as byproducts of water electrolysis using energy from renewable energy sources. This setup enables the combustion of hydrogen with oxygen in argon as the working gas, forming water as the sole product. A potential engine architecture, derived from a heavy-duty diesel engine baseline and its working principle can be seen in the video below.

The consortium has selected a 13-liter heavy-duty engine platform for initial evaluation, focusing on stationary applications due to their reduced complexity. While mobile applications remain a long-term objective, stationary prototypes offer a practical development path.

Thermodynamic simulations indicate that BTE levels of around 60 % are achievable, even when considering the necessary reduction in compression ratio to manage thermal and mechanical stresses specific to the argon cycle. However, these estimates do not yet account the practical efficiency losses caused by contamination of the working gas, such as CO₂ ingress from oil consumption or water vapor from incomplete condensation.

Stay tuned for the Engineering Blog

Don't miss the Engineering blog series. Sign up today and stay informed!